ON JUNE 11, 1947, eight days after the announcement of the Partition, the Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali Khan, issued a firman declaring that Hyderabad State would not accede to either of the newly announced dominions. “The result in law of the departure of the Paramount Power in the near future,” the Nizam asserted, “will be that I shall become entitled to resume the status of an independent sovereign.”1 At 82,698 square miles, Hyderabad State was larger than the provinces of Bengal (77,442) and Bombay (76,443) and, indeed, larger than England and Scotland put together (80,752).2 The Nizam’s landlocked dominions occupied the lion’s share of the Deccan Plateau, sharing a border more than 2,600 miles long with Bombay, Central Provinces and Berar, Bastar, Madras, Mysore, and the Deccan States. With a population of around seventeen million, Hyderabad was larger than any dominion of the British Commonwealth as well as a good number of United Nations member states. The Asaf Jah dynasty had ruled Hyderabad for more than two centuries and laid claim to the legacy of both the Mughal Empire and an even longer history of Muslim rule in the Deccan.

The response to the Nizam’s declaration of independence among Indian nationalists was apoplectic. With a civil war threatening to engulf northern India and with Partition looming, the prospect of further threats to the territorial integrity of the nation-state was alarming. For B. R. Ambedkar, law minister in the Union Cabinet, Hyderabad was “a new problem which may turn out to be worse than the Hindu-Muslim problem as it is sure to result in the further Balkanisation of India” and challenge India’s claim to sovereignty internationally.3 Jawaharlal Nehru observed that “Hyderabad is full of dangerous possibilities.”4 Vallabhbhai Patel explicitly linked his acceptance of Partition to the prevention of Hyderabad’s bid for independence: “When we accepted division, it was like our agreeing to have a diseased limb amputated so that the remaining may live in a sound condition.”5 Hyderabad, the Sardar argued, was “situated in India’s belly. How can the belly breathe if it is cut off from the main body?”6 Patel’s corporeal metaphor was rather well worn, tapping into a deep discursive reservoir regarding a national geography as embodied in the figure of Bharat Mata.7 Yet it was also an inheritance from interwar constitutional debates that grappled with the intractable problem of the Indian states. “India could live if its Moslem limbs in the North-West and North-East were amputated,” the Oxford doyen of imperial history Reginald Coupland noted in 1943, “but could it live without its heart?”8 The Nizam’s firman put this question to the test, ushering in the decisive phase in the struggle over sovereignty in the Deccan that would come to a swift, violent resolution fourteen months later with the Police Action of September 1948.

While the Nizam’s bid for independence was a contingent response to the June 3 Partition Plan, it was also decades in the making. At the time of the Nizam’s firman, Hyderabad was not the only Indian state openly contemplating independence. Bhopal and Travancore also made public intimations to that effect. Jammu and Kashmir, shortly to become a site of violent contestation and an enduring reminder of the fraught legacies of the Raj, had no intention of acceding to either India or Pakistan. The intractable conflict over Kashmir has ever since been internationalized as the territorial locus of enmity between the nation-states of India and Pakistan. Indeed, India referred the Kashmir issue to the United Nations. In contrast, India’s nationalist leaders were anxious to keep Hyderabad a “purely domestic issue,” and they denied that Hyderabad had “any right in international law.”9 It was not coincidental that the Police Action took place as the United Nation’s Security Council began discussions on whether to hear Hyderabad’s appeal.10 Hyderabad was “no longer an international affair,” Patel remarked as Indian forces entered the state on September 13, 1948, but “a States Ministry function.”11

In his June 11, 1947, firman, the Nizam prefaced his claim to “resume the status of an independent sovereign” on the “result in law of the departure of the Paramount Power.”12 From a legal perspective, the Nizam’s claim was in line with a centuries-long history of imperial constitutionalism. Hyderabad had historically played a preeminent role as a sovereign yet subordinate state within the Raj’s imperial constitution. The Indian Independence Act, given royal assent on July 18, was quite clear that the territories of the new dominions of Pakistan and India would, at least initially, be formed out of British India alone.13 The act, moreover, held that the “suzerainty of His Majesty over the Indian States lapses” and with it all “functions,” “obligations,” and “powers, rights, authority or jurisdiction” exercised by the British Crown vis-à-vis the Indian states.14 The act was a unilateral revocation of all treaties and other relations between the British Crown and the Indian states. On the one hand, this represented the fulfillment of a long-cherished goal of the princes: paramountcy was not transferred to, or inherited by, the successor governments of the Raj. On the other hand, by breaking with the frameworks and conventions of imperial constitutionalism, the British betrayal of the Indian states gave Indian nationalists the opportunity to consolidate India into a unitary territorial nation-state. They would be, as V. P. Menon informed a receptive Sardar Patel, “writing on a clean slate, unhampered by treaties” or other legal rights of the states that had confounded interwar constitution-making efforts.15

The Nizam’s firman, then, brought to the fore the fundamental tension of the Raj’s imperial regime of sovereignty: the elaborate jurisdictional edifice of the Raj, on the one hand, and, on the other, the inability of paramountcy to be satisfactorily codified. Treaties, sanads, and other legal documents had, since at least 1857, coexisted with what imperial administrators referred to as “usage” or “political practice.” Paramountcy was ultimately a political fact unconstrained by the law. This constitutive tension between legal and political domains did not simply come to an end in mid-1947. Indeed, it was precisely through such indeterminacy that the Raj was dismantled and the Republic built up. The distinction between the provinces of British India and the Indian states was even maintained in the republican Constitution of 1950. India’s claim to Jammu and Kashmir—and all the other states aside from Hyderabad—rested on the legal standing of the Instruments of Accession signed by the Maharaja and his counterparts from other states. In the case of Hyderabad, nationalist leaders discarded legal arguments in favor of those based on demography, popular sovereignty, and the de facto supremacy of the government of India.

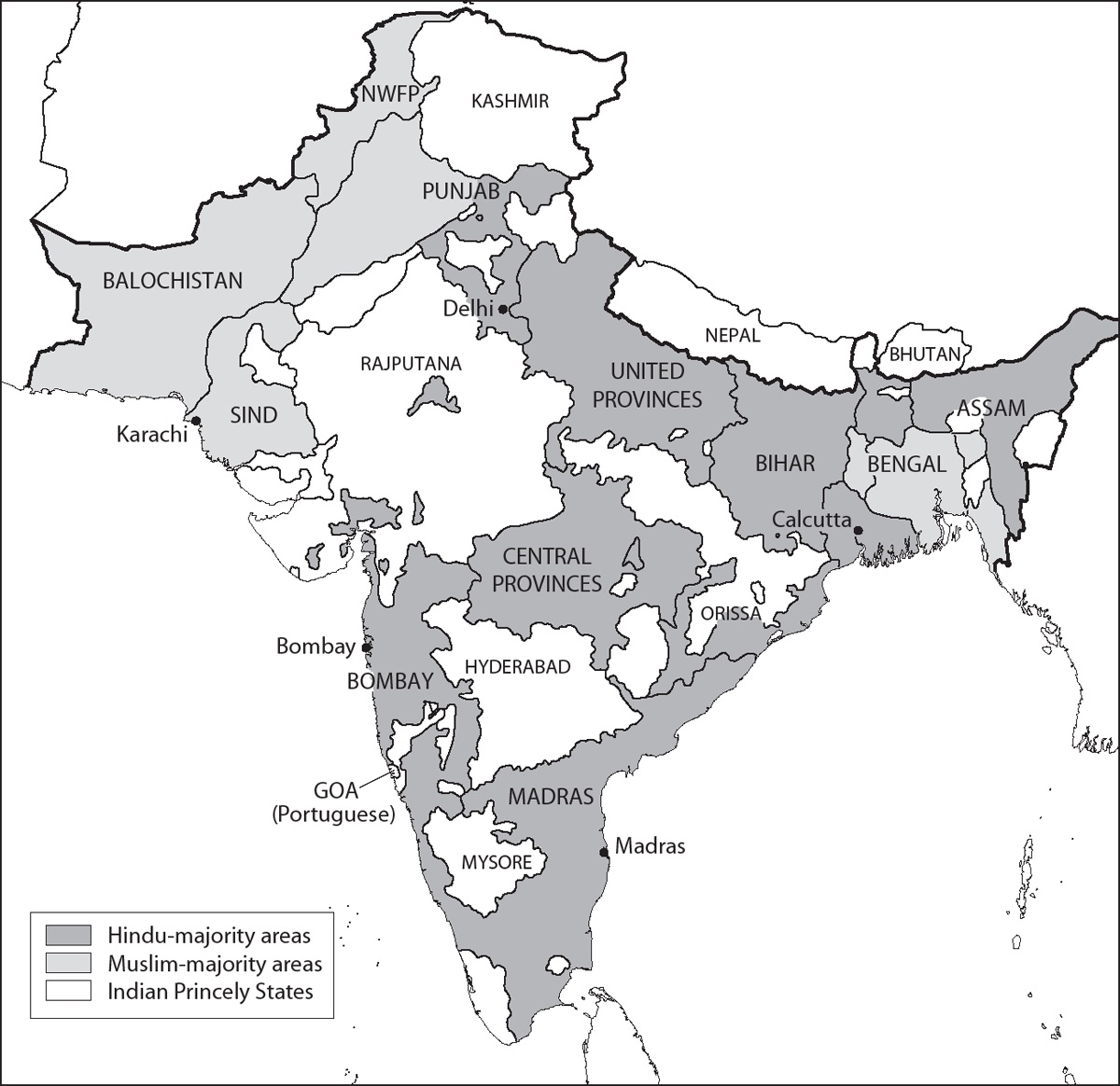

MAP 1. India before Partition in 1947.

There was general consensus that the Nizam and his state possessed and exercised sovereignty before August 1947. What was disputed, however, was the character and quality of that sovereignty and whether, as the Nizam asserted, it “entitled” him to “resume”—after nearly two centuries—the “status of an independent sovereign” within the emergent postwar international order. The Nizam’s bid for independence was the culmination of long-standing efforts to affirm and consolidate his sovereignty, both within his territories and in Britain’s Indian empire more broadly. The ultimate triumph of republicanism over dynastic kingship in India was not preordained, nor was its history merely a staid legalistic narrative. It was, rather, a highly contested, multifaceted, and violent process. Indeed, in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, monarchs not only survived decolonization but were able to expand and consolidate their claims to sovereignty. South Asia was hardly unique in the tensions between nationalist projects of self-determination and the legal ambiguities of imperial regimes of sovereignty.

In their September 1948 appeal to the United Nations, Hyderabad’s representatives argued that, from the date of the Indian Independence Act, Hyderabad, “already a sovereign State, became also independent for international purposes.”16 India’s representative to the Security Council responded that Hyderabad “is not competent to bring any question before the Security Council; that it is not a State; that it is not independent; that never in all its history did it have the status of independence; that neither in the remote past nor before August 1947, nor under any declaration made by the United Kingdom, nor under any act passed by the British Parliament, has it acquired the status of independence.”17 The government of India argued that Hyderabad and other Indian states were not international entities under the system of paramountcy and did not simply earn international status by virtue of paramountcy’s cessation. Hyderabad’s delegates conceded that the Indian states had “no international life” under paramountcy.18 But, they argued, by virtue of the lapsing of paramountcy, Hyderabad had become sovereign as well as independent.

As Eric Beverley has observed, Hyderabad’s case was exemplary of the transition from a world in which sovereignty was often ambiguous and fragmented, where “minor states—sovereign but subordinated—occupied a vast legal gray area,” to a postwar international order premised on “monistic” notions of territorial sovereignty.19 The British united all of India under one imperial system, but the Raj was not a coherent or codified entity. It was marked instead by territorial fragmentation, legal plurality, and layered and dispersed forms of sovereignty. It was a complex institutional matrix, a messy aggregate of legal orders and administrative jurisdictions. This arrangement was an outcome of the contingencies of colonial conquest between 1757 and 1857 and was further elaborated in the decades after the insurrection.20 The British conquest was piecemeal, taking place over the course of a hundred years, during which time the East India Company signed treaties with or otherwise subordinated hundreds of Indian sovereigns and magnates, who would later form the bulk of the Indian “princes.” Following the British reconquest in the wake of 1857–58, these contingent arrangements of conquest were molded into a permanent institutional structure and constitutional order.

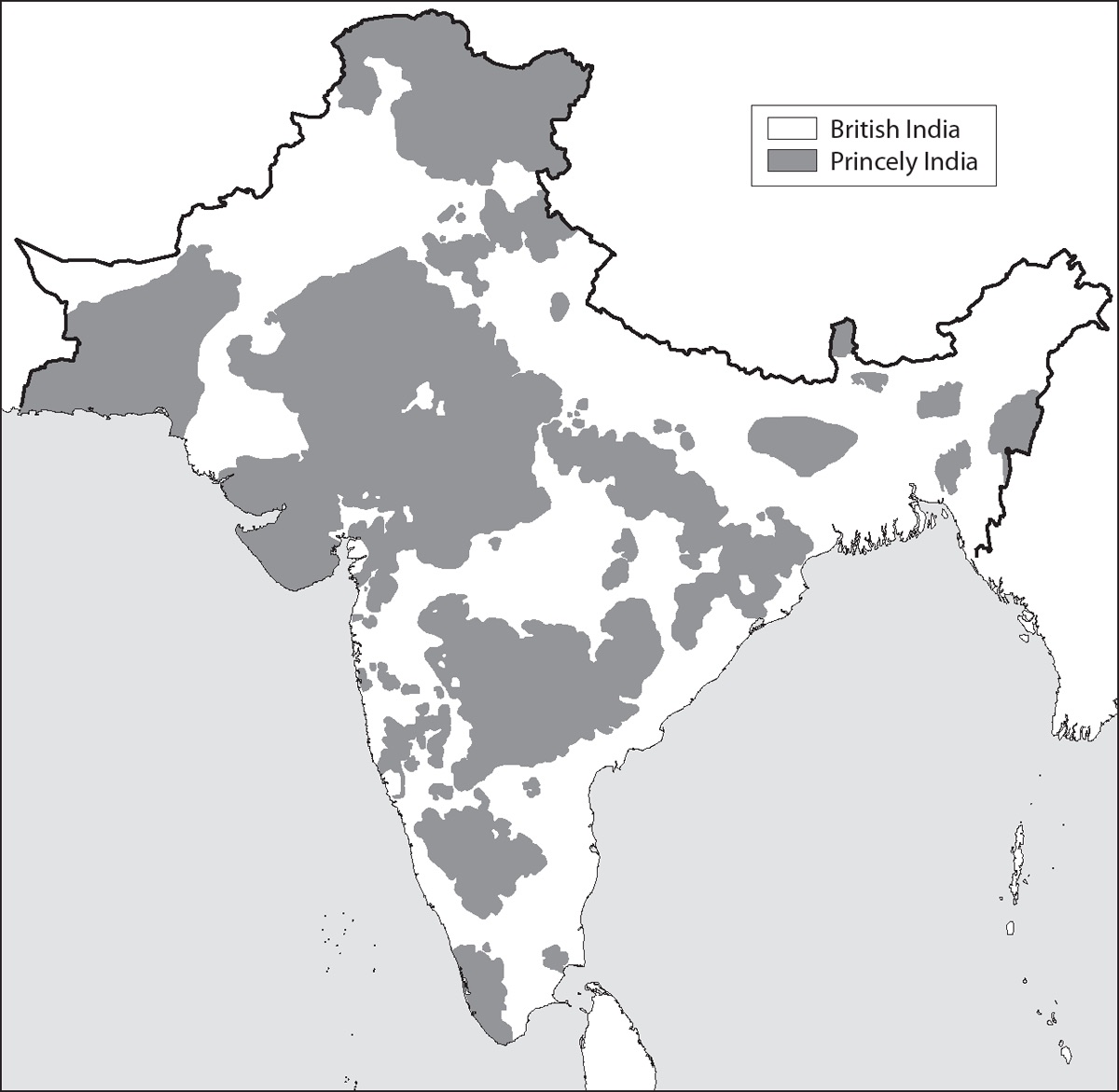

The post-1857 imperial constitution consisted, broadly, of “two Indias,” each internally differentiated: the directly ruled British Indian provinces and the indirectly ruled Indian states. Coexisting and codependent, these two Indias were juxtaposed across the subcontinent, giving the sovereign landscape of the Raj an extraordinary spatial character, one marked by the proliferation of territorial anomalies. The Indian states collectively occupied approximately two-fifths of the total area of the subcontinent. There was a staggering diversity among the states themselves, ranging from small units no larger than a few villages to large polities replete with the trappings of modern administration. All were autocracies, as was the Raj more broadly. They exercised varying degrees of internal autonomy; the vast majority were petty “semijurisdictional” or “nonjurisdictional” rather than “full-powered” states.21 All states ceded rights of external affairs and of the ability to wage war to the British.

Despite their enormous differences, the states were lumped together into the single category of “princely,” “native,” or “Indian” states—a “uniformity of terminology” that posed significant challenges to late colonial constitution-making efforts.22 Indeed, their legal, constitutional, and institutional qualities differed wildly. Only around forty major states had formal treaty relations with the British. The government of India did, however, issue sanads (certificates of protection and recognition) and letters of understanding to many states lacking formal treaty rights.23 The British never systematized their relations with the princes, adopting instead an ad hoc approach that dealt separately with each state or groups of smaller states through the Political Department, which was under the direct control of the viceroy as the Crown representative. The underlying principle of this system was the concept of the “paramountcy” of the British Crown. Although treaties, sanads, and other legal documents suggest that paramountcy was a legal, contractual, and consensual relationship, ultimately it was founded on British military supremacy and the right of conquest. “The paramount supremacy of the British Government,” the government of India proclaimed in 1877, “is a thing of gradual growth; it has been established partly by conquest; partly by treaty; partly by usage.”24 The right of the government of India to intervene in the internal affairs of states (regardless of treaty status) in the event of perceived misrule or disorder was an essential, if infrequently exercised, dimension of paramountcy. Despite the routinization of paramountcy after 1857, however, the Raj was never codified into a unified legal architecture. This “indefinite suzerainty” left “largely unresolved certain fundamental questions of conquest, sovereignty and subjecthood.”25 The imperial constitution of the Raj relied instead on administrative practice and convention, what imperial administrators referred to as “usage” or “political practice.” Henry Maine observed that “no general rules” could apply to the division of sovereign powers between the British and the Indian states. These would be deduced instead “from de facto relations” between the paramount power and individual states.26

MAP 2. British India and Indian Princely States.

Beginning in 1759, the Nizams of Hyderabad signed more than a dozen treaties with the British. Hyderabad’s position within the Raj was characterized by “hierarchical relations in the political domain” and “the language of reciprocity in the legal sphere.”27 The initial treaties of the late eighteenth century were primarily military in nature, as the expansionist East India Company moved to vanquish first its European rivals and then Mysore and the Marathas. The alliance with Hyderabad was a crucial factor in British victories over Tipu Sultan and the Marathas, ensuring British dominance in peninsular India and, perhaps, the subcontinent as a whole. In 1766, a treaty of “honor, alliance and friendship . . . and mutual assistance” distinguished Hyderabad’s sovereignty from that of the Mughals.28 The Treaty of Perpetual and General Defensive Alliance signed in 1800 aimed at the “reciprocal protection of their respective territories” and held the Nizam to be an “equal partner with the Company.”29 An 1803 treaty guaranteed British recognition of Hyderabad “until the end of time.”30

Hyderabad was, as Kavita Datla argued, “absolutely central to the forging of the British imperial order, and generative of the very practices that came to characterize colonial expansion and governance.”31 The idea of paramountcy as a historical partnership of sovereignty—of empire as collaboration—persisted even as the hierarchical relationship between the British and the Indian states was affirmed within the post-1858 imperial constitution.32 The Nizam’s loyalty in 1857 was a crucial factor in the ability of the British to hold on to their Indian empire. After the fall of Delhi, the governor of Bombay telegraphed the resident at Hyderabad that “if the Nizam goes, all is lost.”33 When Hyderabad’s prime minister Sir Salar Jung later visited England he was hailed as the “saviour of Indian empire.”34 It was after the Mutiny that the Nizam became referred to as “Our Faithful Ally,” a title officially bestowed to Mir Osman Ali Khan after the First World War.35 The “Native Chief,” for Lord Curzon, was a “colleague and partner”; on another occasion he described “the Princes” as not simply “appendages of Empire, but its participators and instruments.”36 For Lord Hardinge they were “colleagues in the great task of imperial rule.”37 Indeed, Mir Osman Ali considered Hyderabad’s contributions to both World Wars a continuation of his state’s historically central and constitutive position within the Raj’s imperial regime of sovereignty.38

All the same, Hyderabad was not immune to the power dynamics of the military and financial relationships that developed out of the East India Company’s subsidiary alliance system.39 Hyderabad’s “friendship” with the British was, in practice, not a relationship among equals. From as early as the 1790s, Hyderabad was sovereign but not independent. Certainly, from the end of the Third Anglo-Maratha War in 1818, at the latest, the British were a class apart from any other sovereign state in India.40 After 1858, Lord Canning wrote, “The distinction between independent and dependent States lost its significance.”41 Like other subordinate sovereigns, the Nizam of Hyderabad was forbidden to establish formal relations or go to war with any other state, either outside or within the Indian Empire. The British arrogated the right to intervene in Hyderabad’s internal administration, although the influence of the resident over the Nizam tended to wax and wane over time. Over the latter half of the nineteenth century, Hyderabad established itself as the “premier state” within the Raj’s imperial regime of sovereignty, the first among unequals. Mir Osman Ali Khan, who became Nizam in 1911, sought to further distinguish Hyderabad from other Indian states, positioning himself for his eventual bid to “resume the status of an independent sovereign.”

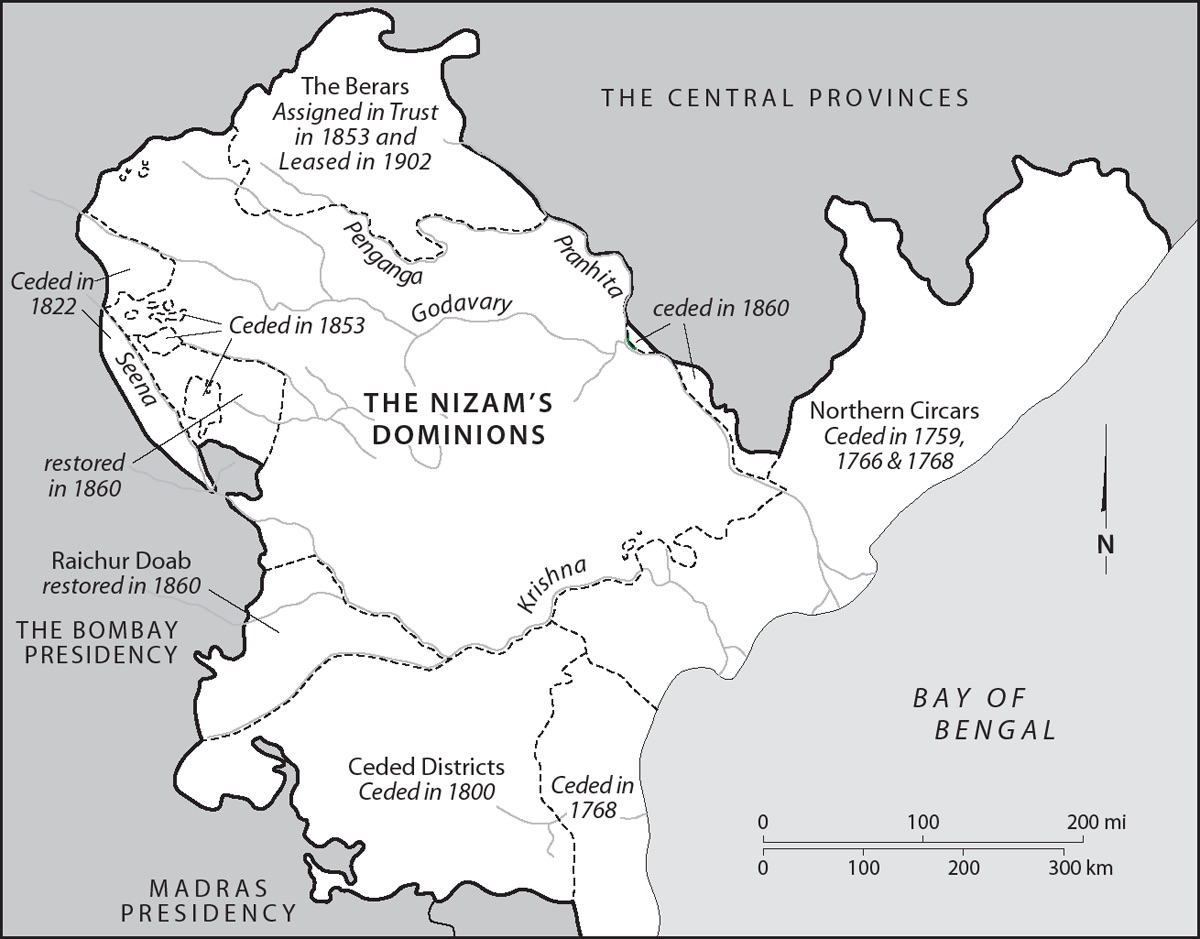

Over the first half of the nineteenth century, Hyderabad’s subsidiary alliance with the British consistently eroded the financial stability of the state, which in turn allowed the British to demand concessions. As a result, the territorial contours of Hyderabad State were almost constantly changing. The Nizams ceded territories to the British, and, on occasion, territories were restored to them. As a result, the border between the Nizam’s dominions and British India was a sprawling frontier zone, marked by juxtaposed jurisdictions and territorial enclaves.42 It was this frontier that would become a site of contestation between competing projects of sovereignty as Indian nationalists and revolutionaries challenged Hyderabad’s commanding position in peninsular India from 1938 onwards. After the First World War, Mir Osman Ali Khan sought the restoration of territories ceded to the British as part of his efforts to affirm and consolidate the sovereignty of his state and his dynasty. Indeed, he used each phase of constitutional negotiations between 1919 and 1947 to push territorial claims, most notably with respect to Berar.

Hyderabad became landlocked after ceding claims to areas on the Coromandel coast, including the port town of Masulipatnam, in 1759, and the Northern Circars through treaties in 1766 and 1788.43 The Nizam abandoned his claim to peshkash in the latter areas in 1823. In 1800, the Nizam lost the Ceded Districts (Anantapur, Kadapa, Karnool, Ballari, and parts of Tumakuru and Davanagere) that he had gained in 1792 from the Treaty of Seringapatam. But it was the fertile cotton-growing districts of Berar, the richest part of the Nizam’s dominions, that became a point of long-standing dispute. Berar exemplified the ambiguities, tensions, and contradictions of the Raj’s imperial regime of sovereignty. According to an 1853 agreement, Berar was put under British administration in exchange for relief from the crushing debt placed on Hyderabad by the maintenance costs of the Hyderabad Contingent as per the terms of the subsidiary alliance. Berar was to be “held in trust” by the British, yet the Nizam maintained his claim to sovereignty over the “Assigned Districts,” as well as to their surplus revenue.44

MAP 3. The Nizam’s Dominions.

In that same 1853 agreement, the Nizam ceded the districts of Osmanabad and Raichur, only to have them returned in 1860 as a reward for his loyalty in 1857–58. Yet the British refused to return Berar. In 1866 and again in 1873, the Nizam’s diwan, Salar Jung, officially requested the restoration of Berar, but he was repeatedly rebuffed.45 Salar Jung reminded his British counterparts that Berar was “the garden of our sovereign’s country, which was taken from him, under circumstances of humiliation to him and to us which are still vividly imprinted on the memory of the Hyderabad people.” He vowed never to “cease from sorrowing or relax our anxious efforts” to have Berar returned to Hyderabad.46 True to his word, Salar Jung again requested restoration in 1876. The government of India responded that “in the life of states as well as of individuals, documentary claims may be set aside by overt acts” and that “great political changes not only introduce new rights and new duties, but may ever modify the interpretation of treaties or render them altogether void.”47 Here we have an enunciation of paramountcy as an evolving political fact existing beyond and not beholden to treaties or, indeed, the law more generally. Viceroy Reading would, famously, strike a similar chord when Mir Osman Ali Khan raised the Berar issue again in the early 1920s.

Nizam Mahboob Ali Khan, Osman’s predecessor, intended in 1901 to ask the viceroy for the restoration of Berar as a favor to Hyderabad on the occasion of the coronation of Edward VII. The viceroy, Lord Curzon, repeatedly informed the Nizam that Berar was not going to be restored, despite Hyderabad’s generous support for the British effort in the Boer War. The Nizam was instead induced to lease the districts to the British in perpetuity. A 1902 treaty reaffirmed the Nizam’s “sovereignty” over the “Assigned Districts” while at the same time recognizing the “exclusive jurisdiction” of the British.48 The British agreed to pay the Nizam a fixed sum of Rs. 25 lakhs (2.5 million) per year from Berar’s revenues.49 Although the British administered Berar as part of the Central Provinces, its inhabitants remained subjects of the Nizam. This parceling of sovereignty and jurisdictional authority was exemplary of the fragmented and contingent nature of the Raj’s imperial regime of sovereignty and its territorial order.

The First World War marked a watershed moment for political life in India and, indeed, the colonial world more broadly.50 Millions of Indians were mobilized for the war and suffered more than a hundred thousand casualties. The Indian princes, and the Nizam of Hyderabad most prominently of all, vigorously supported the British effort. It was in this context that the secretary of state for India, Edwin Montagu, committed in August 1917 to the “progressive realisation of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire.”51 This announcement inaugurated a sustained phase of constitutional contestation in late colonial India, one that would conclude in 1947 or, in the case of the Indian states, with the Police Action against Hyderabad in 1948. The 1919 Government of India Act applied only to British India, yet Montagu and Viceroy Chelmsford noted that the reforms “cannot leave the States untouched.”52 Montagu and Chelmsford reiterated the Indian states’ “immense value as part of the polity of India” and assured the princes that “no constitutional changes which may take place will impair the rights, dignities and privileges secured to them by treaties, sanads, and engagements or by established practice.”53 Taking note of the “ambiguity and misunderstanding” concerning the “exact position” of the states, they suggested efforts to “simplify, standardize and codify existing practice for the future.”54

This task of codifying the Raj’s imperial constitution became the dominant imperative of, and would ultimately confound, interwar constitution-making efforts. The basic framework for reforms aimed to unite British India and the Indian states under a federal constitution. The idea of an Indian federation was central to interwar political imaginaries, lending itself to divergent, innovative, and radical visions of India’s future. In many of these visions, not least the official British one, the Indian states took on a new and integral role.For Montagu and Chelmsford, the only practicable model for codifying the Raj was “some form of federation.”55 Over the course of the 1920s, the idea of federating the Raj became something of an elite consensus. Indeed, federalism provided for Indians and the British alike a common language for elaborating questions of rights, democracy, and sovereignty. The 1919 Constitution was a transitional one; it was a step toward a “progressive realization.” As such, it opened up both a wide range of possibilities and a good amount of uncertainty. Federation pointed to a likely scenario in which the provinces of British India would be democratized at the same time as the sovereignty and autonomy of the Indian states would be put on sounder legal footing. Indeed, reconciling the distinct theories of political legitimacy and territorial authority of the “two Indias” within a heterogeneous constitutional structure was precisely the intent behind the “Federation of India,” the centerpiece of the 1935 Government of India Act.

The pressure for constitutional reform placed on the British by Indian nationalists at once enabled and posed risks for a dependent sovereign, like Mir Osman Ali Khan, who aspired to be an independent sovereign. The newfound all-India relevance of the Indian states spurred, for the first time, collective action among the princes. The Chamber of Princes was established by royal proclamation in 1921 as a consultative body to the viceroy. The king-emperor reiterated his “determination ever to maintain unimpaired the privileges, rights and dignities of the Princes of India.” This pledge was to remain “inviolate and inviolable.”56 The Chamber had 108 member states and another twelve seats reserved for the representation of an additional 127 smaller states. Excluded from the Chamber entirely, but still considered Indian states, were 327 estates, jagirs, and other petty entities, of which 287 were located in Gujarat and Kathiawar.57 The Nizam, seeking to distinguish himself from his princely counterparts, stood aloof from the Chamber.

The Nizam saw the end of the First World War and the inauguration of constitutional reforms as an opportunity to consolidate and even expand his claims to sovereignty. He chose to pursue two objectives: to secure territory and to shore up the legitimacy of his dynasty. He emerged from the war with two new official titles: “Faithful Ally of the British Government” and “His Exalted Highness.” The latter title especially worked to confirm Hyderabad’s status as the “premier” state of the Raj and to distinguish the Nizam from other subordinate sovereigns. His gun salute was raised from fourteen to twenty-one, the most of any of the princes. In 1922, as Gandhi’s first India-wide mobilization and boycott was roiling the country, the Nizam hosted the Prince of Wales, the future king-emperor, in an elaborate ceremony. The Nizam aspired, without much success, over the course of the 1920s and 1930s, to acquire the title of king.58 Beginning in 1918, a series of constitutional, institutional, and economic reforms sought to further equip Hyderabad with the trappings of a modern state.

The Nizam also sought the restoration of territories ceded by his ancestors. In 1923, he wrote to Viceroy Reading asking for the restoration of Berar as a gesture of goodwill in light of his support for British war efforts.59 The Nizam contended that excepting “matters related to foreign powers,” the “Nizams of Hyderabad have been independent in the internal affairs of their State just as much as the British Government in British India.” Hyderabad and the government of India were partners in the Raj: the two governments “stand on the same plane without any limitations of subordination of one to the other.” In addition to petitioning the viceroy, the Nizam reached out to other princes and even to nationalist leaders, including Gandhi. He promised to “grant autonomy to the inhabitants of Berar” if it became “an integral part of the Hyderabad State.” The Mahatma, however, declined to engage with the Nizam.60

In 1926, Reading responded to the Nizam’s letter regarding Berar with a classic statement on paramountcy: “The Sovereignty of the British Crown is supreme in India, and therefore no Ruler of an Indian State can justifiably claim to negotiate with the British Government on an equal footing. Its supremacy is not based only upon Treaties and Engagements but exists independently of them.”61 To add insult to injury, Reading lumped the illustrious head of India’s most populous state, a dynasty that had origins in the Mughal Empire, in the same category with petty estate holders and jagirdars: “The title of Faithful Ally, which Your Exalted Highness enjoys, has not the effect of putting your Government in a category separate from that of other States under the Paramountcy of the British Crown.”62 As a further humiliation, Reading undermined the Nizam’s internal autonomy by imposing personnel on his state’s administration, thus restricting the Nizam’s field of action even within his own state. The key posts of director-general of revenue and director-general of police were to be filled by British officers officially deputed by the government of India. The government of India also installed a representative as a member of the Nizam’s executive council and, further, reserved the right to approve all future appointments to the council.63 The message was clear: the Nizam and the British did not “stand on the same plane.”

The public humiliation of the Nizam alarmed the Chamber of Princes, who pressed the government of India to establish “permanent political machinery” for “regulating the relations of the States to the Crown and to the Government of British India, with a view permanently to protecting the rights of the States.”64 The Chamber argued that their sovereign prerogatives as delineated in treaties, engagements, sanads, and other legal documents had been undermined over time by usage and political practice. Most important of all, they wanted assurances that paramountcy could not, and would not, be transferred from the British to a federal government run by Indians or indeed any other successor government. They argued, crucially, that their constitutional relationship was with the British Crown and not with the Government of India. Thus they could not be compelled to join a potential Indian federation without their explicit consent.65

Reading’s successor, Lord Irwin, appointed the Indian States Committee in 1928 to evaluate the constitutional standing of the Indian states. Known as the Butler Committee, its report, submitted to Parliament in 1929, made a number of interventions that would prove consequential to constitution-making efforts in the following years. The report insisted that paramountcy was “impossible to define.” Their tautology—“Paramountcy must remain paramount”—offered little clarity.66 Paramountcy was a historical and thus essentially political fact “based upon treaties, engagements and sanads supplemented by usage and sufferance and by decisions of the Government of India and the Secretary of State embodied in political practice.”67 The report emphatically supported the virtually unlimited conception of paramountcy in Reading’s 1926 letter to the Nizam, adding further that usage “lights up the dark places of the treaties.”68 Paramountcy was not “a merely contractual relationship, resting on treaties made more than a century ago,” but rather a “living, growing relationship shaped by circumstances and policy, resting . . . on a mixture of history, theory and modern fact.”69 Paramountcy, as a theory of imperial sovereignty, exceeded the limits of the law.

The Indian states, seeking a firmer legal basis for their constitutional claims to sovereignty, were largely disheartened by the Butler Committee’s conclusions. Yet, significantly, the committee supported the Chamber’s claim that the constitutional standing of the Indian states arose out of their relationship with the British Crown rather than the government of India.70 As a result, the Indian states could “not be handed over without their agreement” to any new government brought into being in British India. Paramountcy could not be transferred to “a new government resting on a new and written constitution.”71 Thus was born the princely veto.72 The formation of an all-India polity required the consent of the Indian states. The Butler Committee determined, moreover, that in the event of “widespread popular demand for change, the Paramount Power would be bound to maintain the rights, privileges and dignity of the Prince.” This commitment was affirmed with the Indian States (Protection) Act of 1934, which intended to assuage princely concerns regarding federation by guaranteeing the states protection from activities organized in British India and by imposing penalties on press statements exciting hatred, contempt, or disaffection for state administrations.73

The 1919 Constitution was intended as a transitional one. As the next step in India’s “progressive realisation” of responsible government, the Indian Statutory Commission chaired by John Simon was established in 1927. Their report, submitted to Parliament in 1930, concluded that “the ultimate constitution of India must be federal, for it is only in a federal constitution that units differing so widely in constitution as the provinces and the States can be brought together while retaining internal autonomy.”74 The Simon Commission recommended another transitional constitution, one that would establish a legal-institutional framework for the federation-to-be: “It’s accomplishment must remain a distant ideal.”75 The princely veto was maintained: “The States cannot be compelled to come into any closer relationship with British India.” The new constitution, instead, should provide “an open door whereby, when it seems good to them, the Ruling Princes may enter on just and reasonable terms.”76 They endorsed the Butler Committee’s conception of paramountcy and recommended, moreover, that it be vested in the individual of the viceroy as Crown representative rather than the government of India. The states, moreover, would not be required to make any internal reforms. In the official British imagination, then, federation would be a codification and shoring up of the extant imperial regime of sovereignty.

In November 1930, the idea of an all-India federation moved quite rapidly and unexpectedly from a “distant ideal” to an immediate matter of practical concern. At the opening session of the first of three Round Table Conferences convened to develop India’s next constitution, the Indian States Delegation announced an agreement with moderate British Indian leaders to support an all-India federation as a dominion within the British Commonwealth of Nations. Crucially, not only the Chamber representatives but also those from the major states of Baroda, Kashmir, Hyderabad, and Mysore threw their weight behind the idea of federation.77 This development was contingent on a number of factors, most notably the absence of the Congress, who boycotted the conference. Nevertheless, federation was established as the consensus framework for India’s constitutional advance, even if princely support would fracture by 1935. The Indian states, as the princely delegate K. N. Haksar noted, “held the future of India . . . in the hollow of their hand.”78

The 1935 Act maintained the anomalous position of Berar while confirming both British jurisdiction and the “continuance of the sovereignty of His Exalted Highness over Berar.”79 In order to corral the Indian states into the proposed federation, the British offered a number of concessions. In 1936, the Nizam was given the right to be consulted about the appointment of the governor of the Central Provinces, the right to fly the Asaf Jah flag on public buildings in Berar, the right to hold darbars there, an annual payment of twenty-five lakh from Berar’s revenues, and the title of “His Highness the Prince of Berar” for his heir apparent.80 In a visit to Hyderabad, Viceroy Willingdon made it clear that the agreement reaffirmed the Nizam’s sovereignty over Berar, giving “some real as well as ceremonial effect to the sovereignty of the Nizam.” In exchange, the Nizam should “be prepared to accede to federation in respect to his territories known as the Berars.”81 The Nizam also waived his claim for “a free corridor to the sea at Musulipatnam and a permit to develop a port” as per the Hyderabad Commercial Treaty of 1802.82 In a personal letter from “Your sincere friend and Emperor,” Edward VIII wrote to the Nizam in October 1936 that he was “glad to avail myself of this occasion further to recognise the sovereignty of Your Exalted Highness in the territory of Berar.”83 With the 1935 Act and the proposed federation, it seemed as if Hyderabad and other Indian states had succeeded in affirming and securing their sovereignty amid late colonial India’s constitutional transformations. It was in light of this fact that calls for “responsible government” in British India rapidly gave way to a fierce, multifaceted contestation over sovereignty in India over the course of the latter half of the 1930s. New battle lines were drawn as the Congress pitted a republican program of popular sovereignty against the legitimacy of dynastic kingship.

1. Nizam’s firman, June 11, 1947, file no. 68, pt. II, AISPC Papers, NMML.

2. Government of Hyderabad, Census of India, 1941, vol. 21, H.E.H. the Nizam’s Dominions (Hyderabad State), Part I Report (Hyderabad: Government Central Press, 1945), 1.

3. B. R. Ambedkar, statement, June 17, 1947, in Documents and Speeches on the Indian Princely States, ed. Adrian Sever, vol. 2 (New Delhi: B. R. Publishing, 1985), 628–34.

4. Nehru to Sheikh Abdullah, October 10, 1947, in Nehru-Patel: Agreement within Differences. Select Documents and Correspondences, 1933–1950, ed. Neerja Singh (New Delhi: National Book Trust, 2010), 142.

5. Speech at Panthic Conference, Patiala, October 22, 1947, in Vallabhbhai Patel, For a United India: Speeches of Sardar Patel, 1947–1950 (New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, 1967), 11. In an October 30, 1948, speech in Bombay, Patel said, “The price of partition was worth paying for. We suffered grievously as a result of partition. A limb was torn asunder and we bled profusely. But it was nothing as compared to the troubles that would have been in store for us and with which we would have had to put up. I have, therefore, no regrets for accepting partition.” In Vallabhbhai Patel, Sardar Patel: In Tune with the Millions, Birth Centenary ed., vol. 2, ed. G. M. Nadurkar (Ahmedabad: Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Smarak Bhavan, 1975), 36–37.

6. Speech at Junagadh, November 13, 1947, in V. Patel, For a United India, 55–56.

7. Sumathi Ramaswamy, “Maps and Mother Goddesses in Modern India,” Imago Mundi 53 (2001): 97–114.

8. Reginald Coupland, The Future of India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1943), 151–53.

9. V. P. Menon, The Story of the Integration of the Indian States (Calcutta, 1956), 373. The August 23, 1948, letter sent to Hyderabad made this clear: “The Government of India regards the differences between it and Hyderabad as a purely domestic issue and cannot admit that Hyderabad, considering its historic as well as its present position in relation to India, has any right in international law to seek the intervention of the United Nations or any other outside body for a settlement of the issue.” Manchester Guardian, August 30, 1948. In a November 13, 1947, speech at Junagadh days after the state’s accession, Patel stated, “The problem of Hyderabad is the affair of India and India alone.” V. Patel, For a United India, 11.

10. Clyde Eagleton, “The Case of Hyderabad before the Security Council,” American Journal of International Law 44, no. 2 (1950): 277–302.

11. September 13, 1948. In Maniben Patel, Inside Story of Sardar Patel, The Diary of Maniben Patel: 1936–50, ed. P. N. Chopra and P. Chopra (Delhi: Vision Books, 2001), 210.

12. Nizam’s firman, June 11, 1947.

13. Indian Independence Act, sec. 2.

14. Indian Independence Act, sec. 7.

15. V. Menon, Story of the Integration, 95. Menon was constitutional adviser to Mountbatten before his appointment as secretary of the Ministry of States from July 1947. He was a key figure in the negotiations that brought the Indian states into the Indian Union.

16. “Memorandum on the Case of Hyderabad,” in Hyderabad Delegation to the United Nations, The Hyderabad Question before the United Nations (Documents and Other Materials) (Karachi: Civil and Military Gazette, 1951), 16.

17. “Discussion in the Security Council, 16 September 1948,” in Hyderabad Delegation, Hyderabad Question, 62.

18. Hyderabad Delegation, Hyderabad Question.

19. Beverley, Hyderabad, 5.

20. Emphasis in original. Fisher, Indirect Rule.

21. E. W. R. Lumby, “British Policy toward the Indian States, 1940–7,” in The Partition of India: Policies and Perspectives, 1935–1947, ed. C. H. Philips and Mary Doreen Wainwright (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970), 95–103.

22. Edwin Montagu, Report on Indian Constitutional Reforms (London: HMSO, 1918), 242.

23. Ramusack, Indian Princes, 51–52, 255.

24. Gurmukh Nihal Singh, Indian States and British India: Their Future Relations (Benares: Nand Kishore and Bros., 1930), 347.

25. S. Sen, “Unfinished Conquest,” 228.

26. Benton, Search for Sovereignty, 250.

27. Beverley, Hyderabad, 64.

28. Ibid., 65.

29. Karen Leonard, “Palmer and Company: An Indian Banking Firm in Hyderabad State,” Modern Asian Studies 47, no. 4 (2013): 1159–60.

30. Standing Committee of the Chamber of Princes, The British Crown and the Indian States: An Outline Sketch Presented to the Indian States Committee (London: P. S. King, 1929), 25; Beverley, Hyderabad, 66.

31. Kavita Datla, “The Origins of Indirect Rule in India: Hyderabad and the British Imperial Order,” Law and History Review 33, no. 2 (2015): 332.

32. Bernard Cohn, “Representing Authority in Victorian India,” in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 165–210.

33. Dhananjay Keer, Mahatma Jotirao Phooley: Father of Indian Social Revolution (Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, 2002), 78.

34. Ibid.

35. Hastings Fraser, Our Faithful Ally, the Nizam (London: Smith, Elder, 1865).

36. Quoted in S. M. Mitra, Indian Problems (London: John Murray, 1908), 340–42.

37. Harcourt Butler, Sidney Peel, and W. S. Holdsworth, Report of the Indian States Committee, 1928–1929 (London: HMSO, 1929), 20.

38. Datla, “Origins of Indirect Rule.”

39. C. A. Bayly, Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

40. Edward Thompson, The Making of the Indian Princes (London: Oxford University Press, 1943).

41. Taraknath Das, “The Status of Hyderabad during and after British Rule in India,” American Journal of International Law 43, no. 1 (1949): 59–60.

42. Eric Beverley, “Frontier as Resource: Law, Crime, and Sovereignty on the Margins of Empire,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 55, no. 2 (2013): 241–72.

43. Datla, “Origins of Indirect Rule.”

44. V. K. Bawa, The Nizam between Mughals and British: Hyderabad under Salar Jang I (New Delhi: S. Chand, 1986), chap. 5.

45. Ibid., 153–65.

46. Ibid., 162–63.

47. Ibid., 168.

48. K. R. R. Sastry, Indian States (Allahabad: Kitabistan, 1941), 176–77.

49. Bawa, Nizam between Mughals, 172.

50. Erez Manela, The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

51. Montagu, Report, 5.

52. Ibid., 249.

53. Ibid., 244.

54. Ibid., 243–44.

55. Ibid., 240.

56. John Simon et al., Report of the Indian Statutory Commission 1 (Calcutta: Central Publication Branch, 1930), 1:89.

57. Butler, Peel, and Holdsworth, Report, 5.

58. V. K. Bawa, The Last Nizam: The Life and Times of Mir Osman Ali Khan (New Delhi: Viking Penguin India, 1992).

59. MSS EUR F137/35, IOR.

60. Gandhi to Nizam, March 5, 1924, in CWMG, 27:33.

61. Reading to Nizam, March 27, 1926, MSS EUR F137/35, IOR.

62. Ibid.

63. Bawa, Last Nizam, 116, 129.

64. Standing Committee, British Crown, 140.

65. Ibid.

66. Butler, Peel, and Holdsworth, Report, 31.

67. Ibid., 13.

68. Ibid., 29.

69. Ibid., 23.

70. Ibid., 23.

71. Ibid., 31–32.

72. I borrow the term veto from R. J. Moore but differ on the origins; see his “The Making of India’s Paper Federation, 1927–35,” in The Partition of India, ed. C. H. Philips and M. D. Wainwright (London: Allen and Unwin, 1970), 62.

73. Arthur Berriedale Keith, A Constitutional History of India, 1600–1935, 2nd ed. (1937; repr., Allahabad: Central Book Depot, 1961), 451.

74. Simon et al., Report, 2:13.

75. Ibid., 2:197.

76. Ibid., 2:12.

77. Ian Copland, The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917–1947 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), chap. 3; Ramusack, Indian Princes, chap. 8.

78. Copland, Princes of India, 91.

79. The Government of India Act, 1935, pt. 3, chap. 1 (New Delhi, 1936).

80. Copland, Princes of India, 131–32.

81. N. Gangulee, The Making of Federal India (London: Nisbet, 1936), 258.

82. Shafa’at Ahmad Khan, The Indian Federation: An Exposition and Critical Review (London: Macmillan, 1937), 183.

83. October 27, 1936, letter, in Government of Hyderabad, Census of India, 1941, 21:2.